When people come to Japan for the first time, Shintō shrines and Buddhist temples are always on their list of important places to visit. But they do not think about visiting Confucian sites.

This is not because there are no such places in Japan. For example, there is Yushima Seidō (湯島聖堂) in Tōkyō and Kōshibyō (孔子廟) in Nagasaki. It is because the influence of Confucianism in Japanese culture is far less known than that of Shintō and Buddhism.

But even if tourists and the Japanese themselves seem not to realize it, Confucianism is everywhere in Japan. Not as something to worship, but as a way of life. It is in the way people talk to their superiors, or more specifically, in the way students or young researchers interact with their professors. It is in the way social relationships are understood and lived.

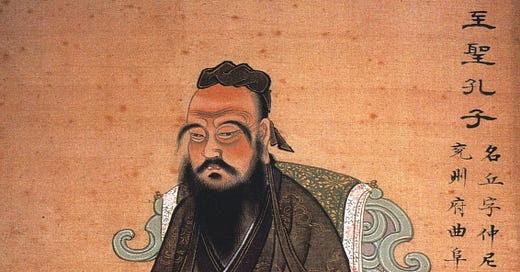

As you know, what we call Confucianism did not originate in Japan, but in China. It is a tradition of thought that began with the teachings of a Chinese intellectual figure: Confucius. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy describes Confucianism as follows:

At different times in Chinese history, Confucius (trad. 551–479 BCE) has been portrayed as a teacher, advisor, editor, philosopher, reformer, and prophet. The name Confucius, a Latinized combination of the surname Kong 孔 with an honorific suffix “Master” (fuzi 夫子), has also come to be used as a global metonym for different aspects of traditional East Asian society. This association of Confucius with many of the foundational concepts and cultural practices in East Asia, and his casting as a progenitor of “Eastern” thought in Early Modern Europe, make him arguably the most significant thinker in East Asian history. Yet while early sources preserve biographical details about Master Kong, dialogues and stories about him in early texts like the Analects (Lunyu 論語) reflect a diversity of representations and concerns, strands of which were later differentially selected and woven together by interpreters intent on appropriating or condemning particular associated views and traditions.

The explanation continues:

This means that the philosophy of Confucius is historically underdetermined, and it is possible to trace multiple sets of coherent doctrines back to the early period, each grounded in different sets of classical sources and schools of interpretation linked to his name. (“Confucius,” 2024)

In other words, there is no single Confucian Philosophy, but rather a body of teachings and interpretations that have contested the legacy of the Chinese thinker.

However, there are core elements that are considered Confucian in every country where it has spread, and it is these core elements that I would like to discuss today in the context of Japanese philosophy and culture. But first, it would be useful to give you some explanation about the spread of Confucianism in Japan.

Confucianism in Japan

Confucianism came to Japan in two main steps:

From the middle of the 6th century along with Buddhism and other elements of Chinese culture.

During the Tokugawa era (1603–1868) in the form of what is now called neo-Confucianism.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Philosophy and Beyond to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.