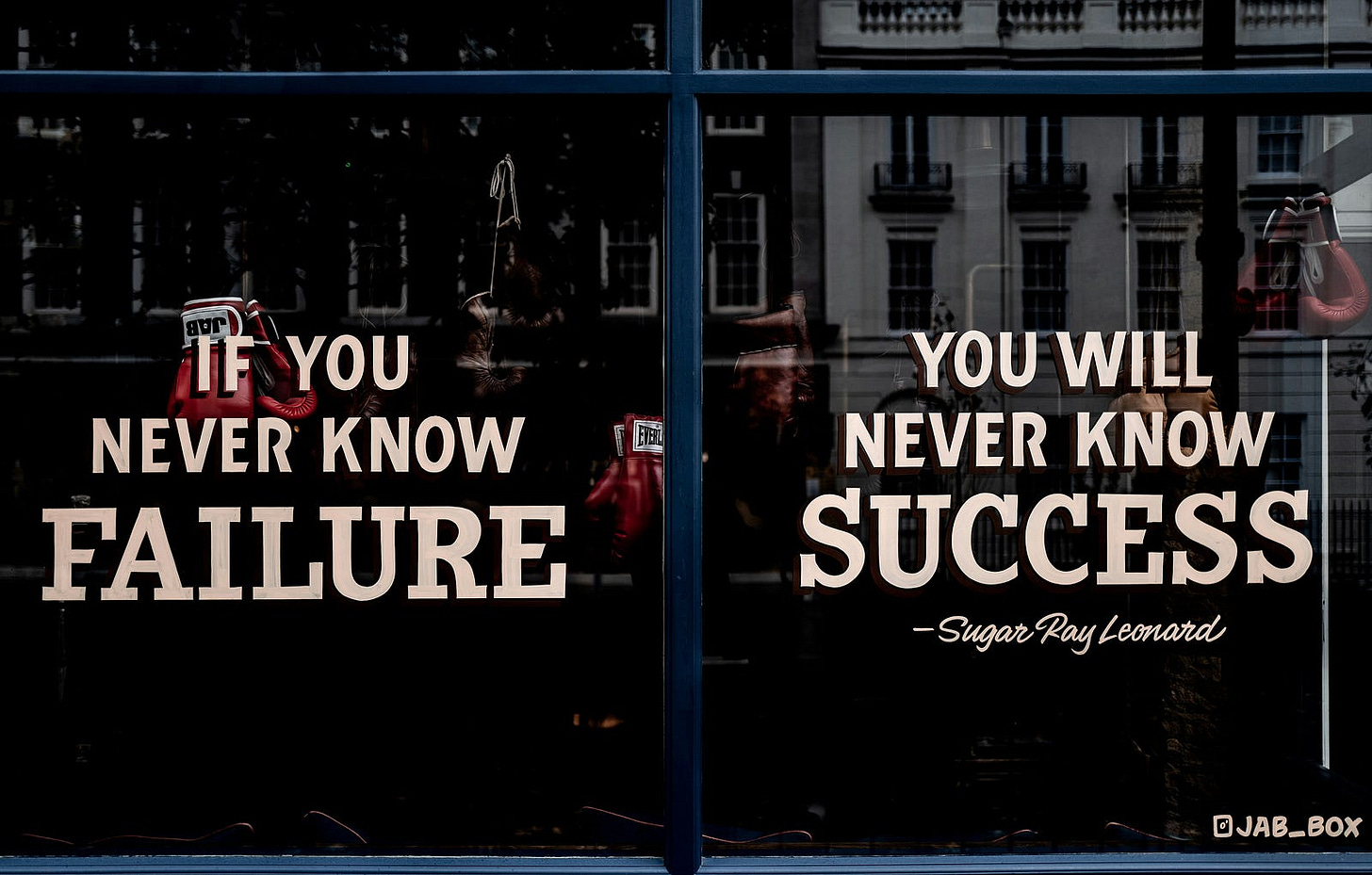

In modern culture, failure has taken on an almost sacred role. From classrooms to boardrooms, TED Talks to Instagram captions, we are told “Failure is the key to success.”

These views affect not only individuals, but also companies. For example, in places like Silicon Valley, a failed startup is no longer seen as a setback but as a sign of resilience.

The slogan “fail fast, fail often” has become so popular that books like Fail Fast, Fail Often: How Losing Can Help You Win have been published. The concept of failure has become dogmatic. The message is so widespread, it feels awkward — if not rude — to push back.

We nod and applaud it, especially when passing it on to the young, because it sounds encouraging. We see failure not just as acceptable, but as necessary. We tend to view it as a rite of passage — a crucial part of the learning process, one might say, disguised as a teacher.

This cultural narrative is comforting. It suggests that nothing is ever truly lost, that all setbacks are ultimately productive, and that time itself will convert our defeats into wisdom.

I have caught myself saying these things too. I have wanted to believe them. After all, we do not want students, colleagues, or friends to feel discouraged. It is easier to offer hope than to admit that life, learning, and effort do not always reward us simply for showing up.

Yet, if you have ever been a bit Cartesian — like that stubborn Frenchman who insisted we begin with doubt — you may feel compelled to question what appears obvious. Before accepting any belief, we must ask whether it is accurate. Is failure truly the seed of success? Have we confused rare exceptions for the rule? Have we confused a poor explanation for a true reason?

Failure Without Learning — and Its Costs

We all know the familiar stories of people like Thomas Edison, J.K. Rowling, and Steve Jobs. They turned failure into success. While these examples may be true, they are exceptions, not norms. Whether one learns from failure greatly depends on the activity.

Consider the following:

Imagine you are at the gym, preparing for your first attempt at a 100 kg bench press. You have trained for over a year. Your personal best is 95 kg, but today you feel strong. You warm up. Your form is solid. You try — and fail.

What did you learn? Perhaps only that you are not yet strong enough. This failure did not change your plan, nor did it reveal what, if anything, went wrong. You were training before and will train again. It merely confirmed a limit you were already approaching.

In this case, if failure has any effect, it is on how you feel: frustrated, motivated, discouraged. But none of these emotions guarantees progress. They may foster patience, but they do not improve strength.

Furthermore, failure can be harmful. In education, athletics, and careers, repeated failure without adequate support often leads to disengagement.

In other words, failure can erode motivation, damage self-confidence, and reinforce ineffective habits. In such situations, the idea that failure is intrinsically valuable is not just inaccurate, it becomes unkind. It shifts responsibility onto the individual while ignoring structural or instructional failures around them.

What Research Shows

The romantic view of failure is not only counterintuitive — it is increasingly contradicted by research. A 2024 article in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General reports findings from eleven studies.

The researchers found that people systematically overestimate how often failure leads to later success. This optimistic bias appears across contexts — from professional exams and medical treatments to addiction recovery and education. Most people who fail do not succeed on the next try; most who relapse do not come back stronger.

Why not? One reason is psychological. Observers tend to assume that people will analyze their mistakes. But most do not. Failure often threatens one’s sense of self. Rather than prompting reflection, it triggers avoidance. People disengage, deny, or simply move on — without learning.

We like to think of people as rational learners. But the data tells a more complicated story.

What is also overlooked is that success teaches us as well. When something works, we receive feedback. We learn what to repeat, reinforce, and trust. We build confidence and clarity. And yet we rarely hear motivational slogans like “Learn from your successes.” Perhaps it sounds too unspectacular.

How to Learn from Failure

Just because people are not usually rational learners does not mean that nothing can be done to turn failure into small victories. In a behavioral study published in Self and Identity in 2005, Kristin D. Neff, Ya-Ping Hsieh, and Kullaya Dejitterat suggest that students can learn more from failure in an academic context through “self-compassion.” They define it as follows:

[S]elf-compassion involves being open to and aware of one’s own suffering, offering kindness and understanding towards oneself, desiring the self’s well-being, taking a nonjudgmental attitude towards one’s inadequacies and failures, and framing one’s own experience in light of the common human experience (…). (K. D. Neff et al., p. 264)

Learning from failure requires a positive attitude toward oneself. Why does this simple attitude work? First, “self-compassionate individuals have an emotionally positive self-attitude that is not contingent on performance evaluations” (K. D. Neff et al., p. 267). In other words, to overcome failure:

Do not take it too seriously. Everyone fails.

Do not worry too much about your score. The most important thing is to stay engaged and willing.

However, the advantage of being self-compassionate is not just about avoiding being stuck on past failure, it is also that it helps to know oneself better. The authors explain:

In addition, self-compassion should be related to higher levels of perceived competence. This is not so much because self-compassion itself enhances perceptions of competence, but because a lack of self-compassion tends to lower perceptions of competence. (K. D. Neff et al., p. 267)

Self-compassion leads to self-knowledge. It also leads to a better understanding of the situation and what can be improved. Moreover, self-compassion is essential not only in case of failure, but also to recognize your strengths. It is a win-win attitude.

The Ethics of Misplaced Encouragement

From a practical standpoint, success — especially small, structured, cumulative success — is a more reliable teacher than failure. Yet, one might still ask: even if the idea is false, isn’t it helpful to believe in the positivity of failure? Doesn’t it help people persevere?

It is a tempting view. But encouraging people to believe that failure will inevitably lead to success — regardless of context or response — places them in a misleading position. It distorts their expectations. It misrepresents how learning works. And it risks transforming what could be brief setbacks into lasting discouragement.

Support matters. But support should not depend on fiction. It is better to say:

“This failure does not define you. What matters is what you do next — and how you do it.”

Conclusion: A Better Way Forward

Success does not require failure. It requires effort, clarity, and continuous adjustment. While failure may occur, it is not what drives progress. Deliberate practice, targeted feedback, and supportive conditions do.

Telling people they must fail to succeed is misleading. In many cases, failure contributes little. In others, it causes harm. Rather than repeating slogans, we should offer guidance. Progress arises from doing the right work in the right conditions.

If we wish to help others grow, we must stop glorifying failure. Some failures are just losses. Others are avoidable. The real difference lies not in failing, but in how we prepare, respond, and persevere.

Let us stop celebrating failure for its own sake. Let us instead champion the quiet, unglamorous work of building success: preparation, support, repetition, feedback, and the courage to continue.

Great text! A lot of interesting thoughts in there.

I just want to add, that apart from what you yourself can do to head for success, your surroundings also have a say.

In my experience, people can say "get back on your horse, you can do it!" if you fail, or they can say "I told you so, this just isn't you".

The number of people you have around you of one and the other kind will often determine if you can keep up the spirit long enough to finally succeed, but it will also influence the actual success level you are at while trying:

Think of a writer who doesn't have many readers – for that very reason, he/she will not get many more. People tend to follow the popular, thereby rewarding success with their attention, and possibly also monetary support and more (when buying the popular writer's books, for instance), while they punish failure by staying at an arms length's distance of the failed.

For all kinds of success that has a place and a definition in society, the society itself is a factor to count in when looking at your chances of reaching it.

Am a fan of the old Chinese proverb: Perseverance Furthers. It doesn't promise anything per se, but it gives a hint, that something may yet come from one's efforts.